Music LessonsChoose the instrument you like to learn more about

A Short History of the Piano

If you have ever played a harpsichord or a clavichord, you know they feel different from a piano. In a piano, a hammer is thrown at the strings when you press a key on the keyboard. The hammer quickly rebounds so the string can vibrate for as long as you hold the key down (or even longer if you use the damper pedal).

The harpsichord is different because the strings are plucked by a plectrum (originally the pointed end of a feather, now made of plastic or other synthetic material). Because the harpsichord plucks the string (as opposed to a hammer striking the string), you are very conscious of the moment the plucking takes place.

The clavichord strikes the string with a metal tangent. Unlike the piano’s hammer that rebounds right away, the tangent stays in contact with the string. So the clavichord, too, has its own feel. There was a keyboard instrument called a virginal, which was a small and simple rectangular form of the harpsichord. The spinet was another small harpsichord-type instrument. These are some of the earliest keyboard instruments. Even the fortepiano, the name given to the earliest piano to distinguish it from the modern pianoforte, or piano, has its own feel—the depth of the key fall is shallow and it takes much less weight to press the key down.

The clavichord strikes the string with a metal tangent. Unlike the piano’s hammer that rebounds right away, the tangent stays in contact with the string. So the clavichord, too, has its own feel. There was a keyboard instrument called a virginal, which was a small and simple rectangular form of the harpsichord. The spinet was another small harpsichord-type instrument. These are some of the earliest keyboard instruments. Even the fortepiano, the name given to the earliest piano to distinguish it from the modern pianoforte, or piano, has its own feel—the depth of the key fall is shallow and it takes much less weight to press the key down.

The Cristofori Pianoforte

The piano itself was invented by Bartolommeo Cristofori in Italy in the year 1709. His was a four-octave instrument (compared to our seven-and-a half octave modern instrument), with hammers striking the strings just as they do on a modern piano. The instrument was invented to meet the need to control dynamics by touch, which could not be done on the harpsichord.

But the early instrument went through many changes before it emerged as the piano we know today. The Cristofori piano was wing-shaped like our grand pianos, with a curved body and a lid that could be raised. There were also square pianos in which the strings ran from left to right as on the clavichord. And by 1800, there were upright pianos whose strings ran perpendicular to the keyboard.

There were many fascinating experiments that produced the giraffe piano, in which the wing-shaped body extended towards the ceiling, or the instrument with six keyboards. A fortepiano built by Johann Andreas Stein had a pedalboard similar to organs. These particular experiments did not lead to the improvement of the piano.

But there have been changes to Cristofori’s 1709 instrument. A double-escapement was introduced by Sebastien Erard in 1821; this allowed fast repetition to be made. Using a cast-iron frame instead of a wooden one was important, as it permitted the use of heavier strings whose tension demanded the strength of a metal frame. These thicker strings gave greater volume and brilliance to the piano. Introduced by Alphaeus Babcock in 1830, cross stringing allowed the strings to fan out over a larger section of the soundboard, again giving more resonance and relieving the crowding of the strings.

How Much Do You Know About Pedals?

On early fortepianos, the knees often manipulated the mechanism we now know as the pedal. For example, you would raise a lever with your knee in order to lift the damper from the string.

Can you imagine a piano with five pedals? These existed. Two of the pedals we still have today. The first pedal—the right pedal—is the damper, which releases the dampers from the strings, allowing them to vibrate. The shift, or una corda, pedal is the one on the left that helps change tonal color and play more softly. Then there were other pedals we do not use today: the moderator, bassoon, and harpsichord or Janissary pedals, which created various effects.

The third pedal on our contemporary pianos is the sostenuto, invented in 1874. The modern piano acquired its essential characteristics by the 1860s or 1870s.

The first piano in America was made by John Brent of Philadelphia in 1774. There have been many piano companies in our country through the years.

The piano is an instrument found in all parts of the world. Its large range, which practically encompasses that of a symphony orchestra, its ability to whisper the pianissimos and thunder the fortissimos, and its magnificent literature, make it one of the most beloved, useful and popular of instruments.

Clarinet History

Clarinets have been around for a very time, although they did not look at first the way they do today. The history of the clarinet goes as far back as the late 1600′s, when an instrument known as a chalumeau was in occasional use in orchestras. The chalumeau is commonly considered to be a forerunner of our modern clarinet, although it bore little resemblance to the ones we play today.

Clarinets have been around for a very time, although they did not look at first the way they do today. The history of the clarinet goes as far back as the late 1600′s, when an instrument known as a chalumeau was in occasional use in orchestras. The chalumeau is commonly considered to be a forerunner of our modern clarinet, although it bore little resemblance to the ones we play today.

The chalumeau was a cane pipe measuring about 20cm (about 9 inches) long. It had seven holes, including a thumb hole, and a range of not much more than an octave. The name chalumeau suggests a French origin for this little instrument. But it was Johann Denner, a leading German woodwind maker, who was credited with improving it, and in doing so inventing the early clarinet. Sometime around 1700, Denner added two keys to the chalumeau, expanding its range by giving it an upper register. He also may have given it a separate mouthpiece and reed.

The history of the clarinet continued to develop as two-keyed clarinets underwent a variety of improvements and were introduced to France and England. By about 1750, the clarinet body had taken the basic shape we see today, but the keywork continued to evolve. In about 1780, five keys were being used. And by 1820 or 1830, clarinets were commonly in use that had 12 or 13 keys. By 1850 or so Boehm system keywork had been introduced. This system, based on the keywork then being used on the flute, managed to eliminated some very difficult fingerings. It is the system most commonly used today although Albert fingering systems are also still in use, primarily in Europe. In North America, it is rare to see a clarinet that does not use Boehm keywork.

In the mid to late 1700′s, composers had begun writing musical pieces that included, or were specifically written for, clarinets. The instrument became much more prominent in the 1800′s, and large volumes of music were written for it in the early 1900′s.

Today, there are minor variations in different models. Manufacturers use slightly different bore diameters and shapes, and occasionally additional keys. Most modern clarinets have 17 or 18 keys.

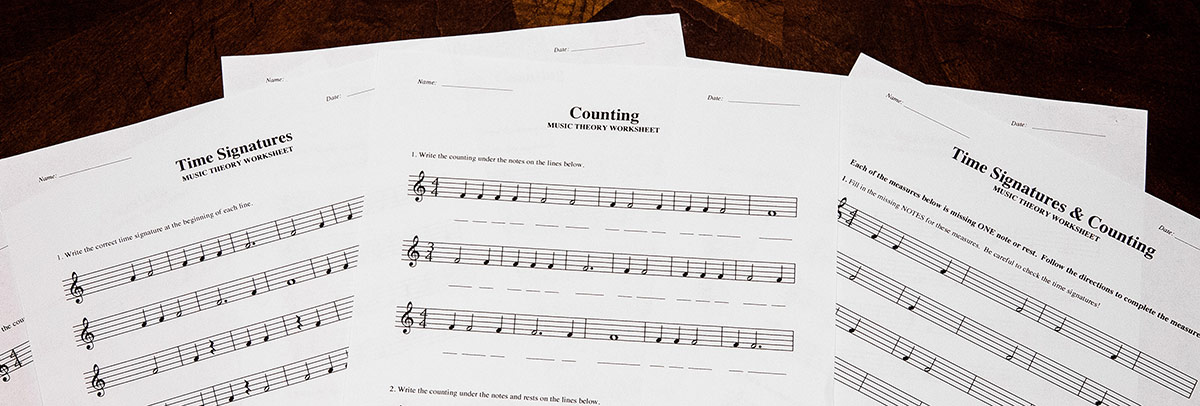

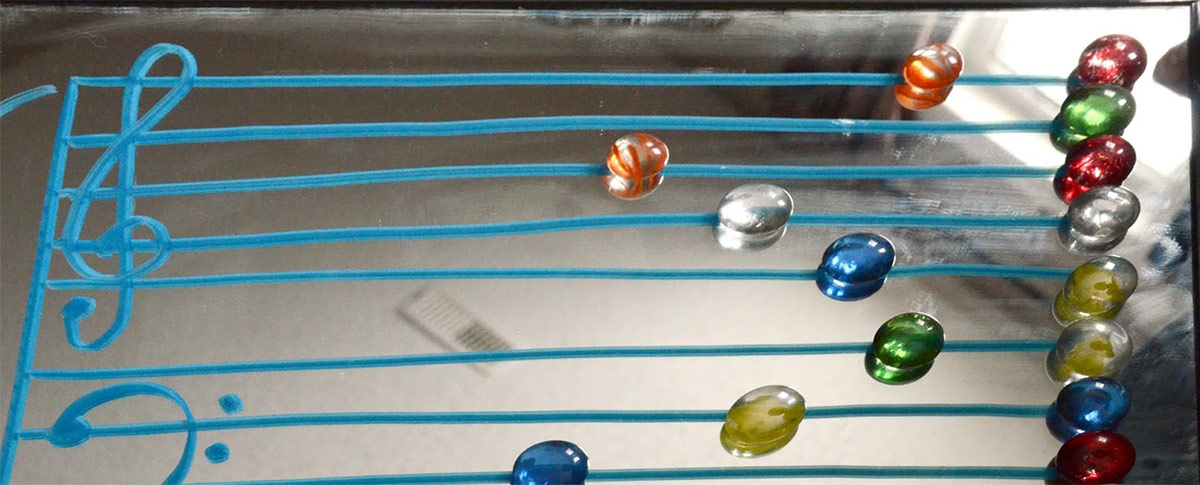

Music TheoryWhy learn music theory?

- moving through the practical music exam grades gives me a sense of achievement,

- having tangible goals is motivating and rewarding,

- getting qualifications will make my CV look better

- I want to know how good I really am

- I want to show off to my friends and family

- My parent/teacher says I have to.

Some people are against exams in principle, and they have a lot of valid arguments. They say that children are put under unnecessary stress, the exams only reflect how you play on one particular day, some teachers only teach the exam pieces and don’t offer a broad spectrum of music to their pupils etc.

However, I tend to disagree with these arguments. I personally think that in most cases putting a child through an exam is something which will usually strengthen their character, not weaken it. Children learn that hard work pays off, they learn how to deal with their nerves, they broaden their experience of life. It’s true that a music exam only reflects what you can do on one day – but the same can be said of all exams and tests. Should we do away with the driving test because it only shows how you can drive for half an hour? And as for teachers who only teach exam pieces, well there will always be bad teachers I guess! I don’t think anyone should be forced into doing a music exam they don’t want to do, but I feel very strongly that it is a very good thing that music exams exist and I believe they are very useful, motivating and can even be fun!

If you want to become a fully-rounded musician you need to know about theory. It is, of course, possible to be a great performer without knowing how to construct a dominant triad in the key of Ab major. But if you CAN construct a dominant triad in Ab major and and can also recognise them in the music you are playing, you will have a deeper understanding of what you are playing – you will be an even better performer!

If you want to go on to study music at university or conservatoire, you’ll need to be able to talk about a piece of music in analytical terms – music theory gives you the basic vocabulary you need in order to do that.

The things you learn when you study for a music theory exam are mostly very logical. When you train to be a performer, you learn how to be expressive. Having both a logical and an expressive side to your playing can only be an advantage. It is also excellent training for your brain, just like doing crosswords or sudoku!

I don’t know why there isn’t a compulsory exam over at the Trinity Board. I would guess that it might be a commercial decision – there will always be music students who, for whatever reason, don’t do a music theory exam but want to take grade six or above in their practical subject. Those students will often transfer to Trinity.

Why don’t many people do the earlier grades in music theory? I think there are several reasons. Lots of teachers and students don’t see the necessity – they only take grade five music theory because they have to. Cost can be an issue of course. Many students don’t even begin to think about theory until they’ve passed their grade five practical and want to move on. But if you’ve passed your grade five music theory exam, why not study for grade six? All the reasons I listed at the beginning of this post also apply to music theory. Once you’ve gained the basics at grade five, why not build on your knowledge and carry on with learning about music theory? Why not set yourself the challenge, gain the qualification, improve your all-round skills as a musician? For those of you who will be applying to university, it’s worth knowing that at grade six and above, music theory exams can count in your UCAS points!

So why take a music theory exam? Here’s a summary of the good points!

- Improve your brain

- Improve your CV and therefore prospects in life

- Motivation and reward

- Discipline in study

- Improve your all-round musicianship

- Broaden your general knowledge

The first electronic sound synthesizer, an instrument of awesome dimensions, was developed by the American acoustical engineers Harry Olson and Herbert Belar in 1955 at the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) laboratories at Princeton, N.J. The information was fed to the synthesizer encoded on a punched paper tape. It was designed for research into the properties of sound and attracted composers seeking to extend the range of available sound or to achieve total control of their music.

The first electronic sound synthesizer, an instrument of awesome dimensions, was developed by the American acoustical engineers Harry Olson and Herbert Belar in 1955 at the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) laboratories at Princeton, N.J. The information was fed to the synthesizer encoded on a punched paper tape. It was designed for research into the properties of sound and attracted composers seeking to extend the range of available sound or to achieve total control of their music. Nobody really knows where the earliest origins of the guitar lie. As long ago as 1400BC the Hittites were playing a stringed instrument with a long neck and a body with a waist. Whether or not this was the direct ancestor of today's guitar we have no way of knowing.

Nobody really knows where the earliest origins of the guitar lie. As long ago as 1400BC the Hittites were playing a stringed instrument with a long neck and a body with a waist. Whether or not this was the direct ancestor of today's guitar we have no way of knowing. Engineers began experimenting with electrically powered instruments, such as music boxes and player pianos, in the 1800s. But the first attempts at an amplified instrument did not come until the development of electrical amplification by the radio industry in the 1920s.

Engineers began experimenting with electrically powered instruments, such as music boxes and player pianos, in the 1800s. But the first attempts at an amplified instrument did not come until the development of electrical amplification by the radio industry in the 1920s. It is believed that the violin originated from Italy in the early 1500s. It is believed to have evolved from the fiddle and rebec, both were bowed string instruments from the Medieval period1. The violin is also believed to have emerged from the lira da braccio, a violin-like instrument of the Renaissance period2. The viol, which came before the violin, is also closely related.

It is believed that the violin originated from Italy in the early 1500s. It is believed to have evolved from the fiddle and rebec, both were bowed string instruments from the Medieval period1. The violin is also believed to have emerged from the lira da braccio, a violin-like instrument of the Renaissance period2. The viol, which came before the violin, is also closely related. To create instruments that played in a lower register, instrument makers experimented with ways to expand the size of the viola da braccio. They were able to increase the string length and bass response, but it soon reached the point where the instruments could no longer be held in the arms. These bass instruments were now positioned on the floor between the knees or in front of the player.

To create instruments that played in a lower register, instrument makers experimented with ways to expand the size of the viola da braccio. They were able to increase the string length and bass response, but it soon reached the point where the instruments could no longer be held in the arms. These bass instruments were now positioned on the floor between the knees or in front of the player. Sax grew up in the trade of instrument making. Sax's father was an expert in instrument making. By the age of six, Sax had already become an expert in it as well. Sax, being the musician he was, became aware of the tonal disparity between strings and winds: moreover, that between brasses and woodwinds. The strings were being overpowered by the winds and the woodwinds were being overblown by the brasses. Sax needed an instrument that would balance the three sections. His answer to the problem was a horn with the body of a brass instrument and the mouthpiece of a woodwind instrument. When he combined these two elements, the saxophone was born.

Sax grew up in the trade of instrument making. Sax's father was an expert in instrument making. By the age of six, Sax had already become an expert in it as well. Sax, being the musician he was, became aware of the tonal disparity between strings and winds: moreover, that between brasses and woodwinds. The strings were being overpowered by the winds and the woodwinds were being overblown by the brasses. Sax needed an instrument that would balance the three sections. His answer to the problem was a horn with the body of a brass instrument and the mouthpiece of a woodwind instrument. When he combined these two elements, the saxophone was born. On display in the National Archaeological Museum of Greece is the tambouras of General Makriyiannis, hero of the 1821 Greek revolution. This tambouras bears the main morphological characteristics of the bouzouki used by the rebetes playing rebetika songs.

On display in the National Archaeological Museum of Greece is the tambouras of General Makriyiannis, hero of the 1821 Greek revolution. This tambouras bears the main morphological characteristics of the bouzouki used by the rebetes playing rebetika songs. Chinese history books trace back to the very birth of music itself, an event pinpointed in the Book Of Chronicles (Schu-Ching) as occurring during the reign of the legendary "Yellow Emperor", Huang Ti, around the year 3000 B.C. Huang's other accomplishments included the invention of boats, money, and religious sacrifice. He is said to have sent the noted scholar Ling Lun to the western mountain regions of his domain to find a way to reproduce the song of the phoenix bird. Ling returned with the cheng (or sheng), and captured music for mankind, taking the first step toward the genesis of the accordion.

Chinese history books trace back to the very birth of music itself, an event pinpointed in the Book Of Chronicles (Schu-Ching) as occurring during the reign of the legendary "Yellow Emperor", Huang Ti, around the year 3000 B.C. Huang's other accomplishments included the invention of boats, money, and religious sacrifice. He is said to have sent the noted scholar Ling Lun to the western mountain regions of his domain to find a way to reproduce the song of the phoenix bird. Ling returned with the cheng (or sheng), and captured music for mankind, taking the first step toward the genesis of the accordion. Japanese FlutesThe oldest flutes found, are thousands of years old and made of bones. These flutes were used during hunting and in magic rituals.

Japanese FlutesThe oldest flutes found, are thousands of years old and made of bones. These flutes were used during hunting and in magic rituals. The pickup - designed because the double bass was often drowned out by the brass sections of jazz bands.

The pickup - designed because the double bass was often drowned out by the brass sections of jazz bands. The baglamas is the smallest instrument in this group. It has three double-course strings and is tuned an octave higher than the bouzouki. It originated at a time when the rebetes were persecuted by the authorities and their instruments and music were forbidden. It is known as the bouzouki of the prison, where the rebetes started making bouzoukia small enough, so that they could easily be concealed in the cells.

The baglamas is the smallest instrument in this group. It has three double-course strings and is tuned an octave higher than the bouzouki. It originated at a time when the rebetes were persecuted by the authorities and their instruments and music were forbidden. It is known as the bouzouki of the prison, where the rebetes started making bouzoukia small enough, so that they could easily be concealed in the cells. The drum is one the oldest instruments known and was used by many cultures around the world. Djembe drum Primitive tribal societies used to celebrate victory in battle aswell as in ritual dance and worship to their dieties.

The drum is one the oldest instruments known and was used by many cultures around the world. Djembe drum Primitive tribal societies used to celebrate victory in battle aswell as in ritual dance and worship to their dieties.